If you had to name the worst year in American history, which one would come to your mind? How about 1861, when the South seceded from the Union, and the bloody Civil War commenced? Or 1929 when the stock market crashed, heralding the lengthy Great Depression? You might choose 1968 when Vietnam War riots, sit-ins, and the assassinations of MLK and RFK were tearing our country apart. Or 2001, when Islamic extremists staged a brutal attack on our nation toppling the World Trade Center, crippling the Pentagon, and sending a plane with heroic passengers to their deaths in a western Pennsylvania field.

A famous historian pointed to a different year, one that may surprise you as it did me. He said, “From the last week of August to the last week of December, the year 1776 had been as dark . . . a time as any of the history of the country.” (David McCullough)

Did he say “1776?” The glorious year we celebrate whose hallmark was the Declaration of Independence? When I taught college-level U.S. History, I told my students there are certain dates they should know as well as their own birthdays, the most important being July 4, 1776 when the colonies declared their independence from Great Britain. 1776, a year that is sacred to Americans. How could it possibly have been one of the worst years in our history? Why did patriot Robert Morris write to George Washington on New Year’s Day 1777, “The year 1776 is over. I am heartily glad of it and I hope you nor America will ever be plagued with such another.”

Prior to that time, New England’s plucky patriots had managed the British forces headquartered in Boston. They’d inflicted heavy casualties at Lexington and Concord and backed the Red Coats into a siege. Once the British headed south toward New York, however, the nascent country’s terrible year truly began. Beginning with the disastrous Battle of Brooklyn in late August, the British and their Hessian mercenaries decimated the badly-outnumbered, outmaneuvered Americans. The cause of independence hung by a frail thread, except for a miraculous fog that lasted as long as it took for the remaining forces to escape across the East River without waking the sleeping giants. The American army lived to see another day.

However, one disaster followed another, at the battles of White Plains and Fort Washington. General Washington was not at his best in these early engagements. He was indecisive at times and lost his celebrated even temper. Some called for his replacement. One of his most trusted allies questioned him behind his back to Washington’s rival. Those soldiers who remained were reduced to the meanest possible level—starving, half-naked, and sick. For all their sacrifices and trouble, they hadn’t even received the pay they’d been promised. Is it any surprise some deserted to the British?

When Philadelphian Charles Willson Peale joined Washington’s army in early December at the Bucks County encampment, he said the troops looked “as wretched as any men he had ever seen.” One of them was almost totally naked. “He was in an old dirty blanket jacket, his beard long, and his face so full of sores that he could not clean it.” The man was so “disfigured” Peale didn’t realize this was his own brother.

Washington was up against the dissolution of what remained of his army. Enlistments would be up at the end of the month, and precious few men had decided to stay with the beleaguered commander. The general wrote in a letter to his cousin, “Our only dependence now is upon the speedy enlistment of a new army. If this fails, I think the game is pretty near up.”

But who would enlist under such unfavorable conditions?

On paper, Washington had about 7,500 men, but only 6,000 were fit for duty. Illness and freezing conditions had laid hundreds of them low. By contrast, the British had in the tens of thousands at their disposal. Added to this trial, the American Congress had fled to Baltimore when the British threatened to take Philadelphia; two members of Congress threw their allegiance to the British. Many Americans concluded the British were far too powerful an enemy to be overcome and were resigning themselves to remain subjects of the king. Historian David McCullough said, “By all reasonable signs, the war was over and the Americans had lost.”

One Pennsylvania soldier, Thomas Paine, wrote, “These are the times that try men’s souls.”

Washington, however, never gave up, nor did he give in. He knew staging a battle in the bitter cold of winter with men in a dilapidated condition might be considered another bad move, but he had to do something by way of winning to prove the end was not at hand. He shared a plan with a close military advisor to stage a surprise raid on the Hessions stationed at Trenton, New Jersey on Christmas night. When he concluded he said, “For Heaven’s sake keep this to yourself, as discovery of it may prove fatal to us…but necessity, dire necessity, will, nay must, justify an attempt.”

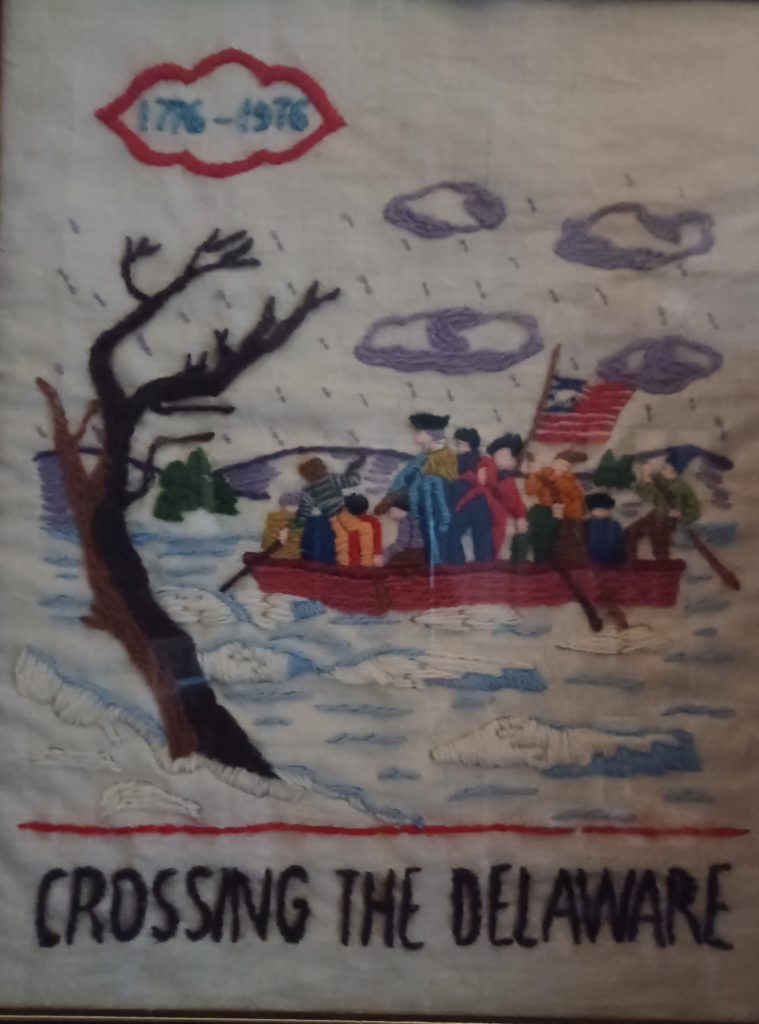

The plan was for about 1,500 men under Washington to cross the Delaware into New Jersey and march south to Trenton, arriving before daybreak. Two other units were to strike directly across from Trenton and from Bristol, Pennsylvania, from the south. A horrific Nor’easter blew in around eleven o’clock, however, making the crossing through ice floes treacherous. The two supporting forces faced ice piled even higher than Washington’s men and weren’t able to get across at all. Washington was left to stage the courageous attack with his men alone while facing brutal conditions. Two actually froze to death on the march to Trenton. When General Sullivan sent a message that the troops’ guns were too wet to fire, Washington told him, “use the bayonet.” He was determined to “push on at all events.”

The German’s Colonel Rall could not have anticipated an enemy attack on Christmas night under such harrowing conditions, and he ended up paying for his miscalculation with his life. Although Washington was behind schedule, his frozen but determined troops dispatched the Hessians in less than an hour. Twenty-one were killed, 90 wounded, and some 900 had been captured. Five hundred escaped. The Americans suffered four wounded and two deaths—the soldiers who’d frozen to death.

David McCullough has written: “The year 1776, celebrated as the birth year of the nation and for the signing of the Declaration of Independence, was for those who carried the fight for independence forward a year of all-too-few victories, of sustained suffering, disease, hunger, desertion, cowardice, disillusionment, defeat, terrible discouragement, and fear, as they would never forget, but also of phenomenal courage and bedrock devotion to country, and that, too, they would never forget.

Especially for those who had been with Washington and who knew what a close call it was at the beginning—how often circumstance, storms, contrary winds, the oddities or strengths of individual character had made the difference—the outcome seemed little short of a miracle.”

I wonder whether I would have had the courage to stick with Washington. I don’t think I would have become a revolutionary at all unless I’d had an experience like John Adams had: after he defended the British participants in the Boston Massacre and got them acquitted, Britain decided that British citizens could not get fair trials in America. But if I had joined Washington, I hope I would have stuck it out. I am stubborn.

Sometimes I wonder as well how I would have responded to those events. I’d like to think I’d have had their courage and yes, stubbornness. I guess the best way we can know is how we respond to what is happening around us in our time. Thanks for your comments, which are always so thoughtful, and appreciated.