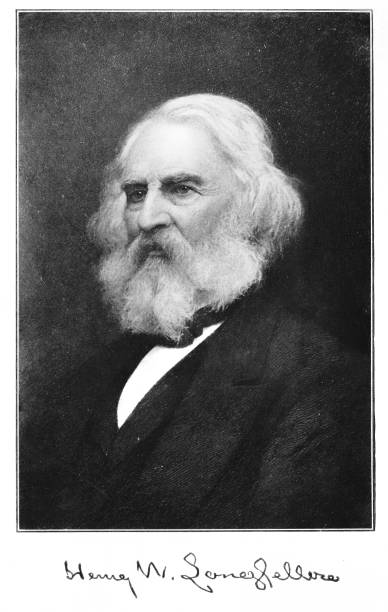

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was born on February 27, 1807 in Portland, Massachusetts. He was educated at Bowdoin College where he became taken with the romantic stories of Sir Walter Scott, and Washington Irving. Longfellow began to write and publish his own poetry in national magazines. When he graduated, he was offered a professorship, if he would first study abroad. For the next ten years he taught and traveled between Europe and the U.S., finally settling down to a position at Harvard. He became America’s most celebrated poet for works including “Evangeline,” “The Song of Hiawatha,” “The Wreck of the Hesperus,” and of course, “Paul Revere’s Ride.”

Longfellow’s first wife, Mary Storer Potter, had died after having a miscarriage while they were traveling in Europe. Seven years later, he married Fanny Appleton with whom he had six children. In 1861, tragedy struck when a dress she was wearing caught fire. Awakened from a nap to her distress, Longfellow rushed to put out the flames, suffering such severe burns himself, that when Fanny died the next day, he was too ill to attend the funeral. Because of scarring to his face and heightened sensitivity to shaving, Longfellow began to grow what became his trademark beard. His grief was so deep at times he didn’t know how he would carry on. Added to his personal loss, the newly-broken-out Civil War weighed heavily on his spirit.

Longfellow was an ardent abolitionist, and his oldest son Charley was eager to do his part. In March of 1863, he left the family home in Cambridge to serve in the Union Army. He impressed himself upon his superiors as a capable soldier and received a commission as a Second Lieutenant in the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry, assigned to Company “G.” He saw action at the Battle of Chancellorsville and narrowly missed the Gettysburg campaign when he came down with “camp fever,” or typhoid, going home to recover, then rejoining his unit in mid-August.

On the first day of that December, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was dining alone at his home when a telegram arrived with news that his son had been severely wounded on November 27 during a skirmish in the Mine Run Campaign.

Longfellow and Charley’s younger brother Ernest immediately set out for Washington, D.C., arriving on December 3. Charley arrived by train two days later. One of the army doctors believed Charley might never walk again. Three other physicians thought he might be greatly improved after a six-month-long recovery.

The famous poet returned to Cambridge in time for Christmas, a 57- year-old widow broken in spirit. On Christmas Day, overwhelmed by his grief, he began listening to the bells from a nearby church. There was something in the persistent and triumphant ringing of those bells that began to pierce his sadness. That’s when he did what all writers do when they are deeply moved—he took up his pen.

He began—

“In despair, I bowed my head. There is no peace on earth, I said, but hate is strong and mocks the song of peace on earth good will to men,” reflecting the state of his soul.

But the poem didn’t end on such a despairing note. As the message of the bells, the very heart of the Christmas story, revived his spirit with the message that God is alive and righteousness will prevail, Longfellow wrote:

“Then pealed the bells more loud and deep…

God is not dead, nor doth he sleep.

The wrong shall fail, the right prevail, with peace on earth, goodwill to men.”

Within a decade (1872), the poem was put to music and has become one of the best-loved Christmas carols.

I wish you and yours the joy and hope of Christmas, which never fails, which will prevail.

Thanks for another interesting blog post.

Steve,

Thank you so much for your encouraging comments, which I’m just now seeing. I so appreciate your touching base!

Rebecca