One of my all-time favorite movies is “National Velvet” from 1944, the story of a young girl who wants to enter her horse into England’s most prestigious horse race. Her father is dead-set against what he considers to be pure folly, but in a tender scene, Velvet’s mother tells her: We’re alike. I, too, believe that everyone should have a chance at a breathtaking piece of folly once in his life. I was twenty when they said a woman couldn’t swim the Channel. You’re twelve; you think a horse of yours can win the Grand National.

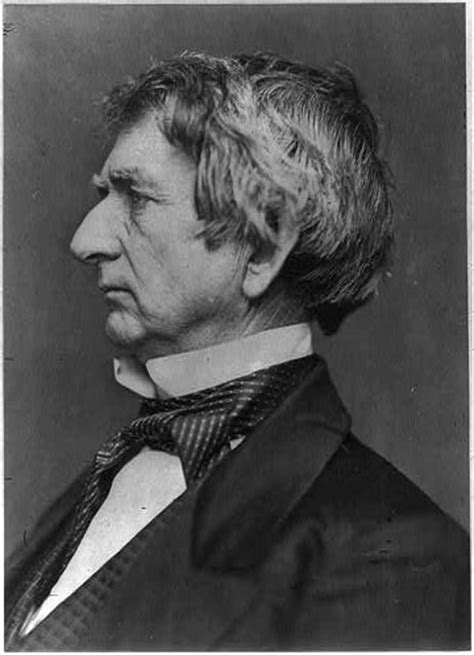

William Seward wasn’t an adolescent girl dreaming of horses and glory, but he was one of the 19th century’s most distinguished statesmen when many critics descended upon him in such a way that his very name became associated with folly. “Seward’s Folly.”

William Henry Seward was born in 1801 in Orange County, New York and at the age of 15, entered Union College, graduating at the top of his class. He went on to become an attorney who was elected to the New York State Senate, then served as New York’s governor for two terms before his election to the United States Senate.

Seward and his wife Frances were champions of those with lesser voices as well as active abolitionists involved with the Underground Railroad. Seward financially supported Frederick Douglass’s North Star newspaper and helped Harriet Tubman buy her home in Auburn, New York.

In his only bid for the Presidency, Seward was defeated by Abraham Lincoln in the Republican primary, but he had a high regard for Lincoln and accepted his invitation to become his Secretary of State. Like the President, Seward was deeply committed to the cause of preserving the Union.

On the night in which Lincoln was assassinated, Seward was at home recovering from a carriage accident when a Confederate conspirator of John Wilkes Booth invaded the Seward home and stabbed the Secretary of State in the face and throat, wounding his son Frederick as they fought him off. Both he and his son healed, and Seward remained in his cabinet position under Andrew Johnson.

In 1867 he negotiated the purchase of Alaska with the Russian foreign minister for 7.2 million dollars, at the time drawing sharp criticism despite the Senate’s overwhelming approval for the treaty. The popular press referred to his actions as “Seward’s folly” and “Seward’s icebox.” They called Alaska “Polar Bear Garden” and “Seward’s Arctic Province.”

He remained undeterred in his opinion that obtaining the territory was the most important measure of his political career but that it would “take the people a generation to find it out.”

He was a man of vision willing to endure temporary scoffing for the sake of gaining for the U.S. a territory rich in natural resources, including gold, petroleum, oil, gas, and fishing, as well as its being of great strategic importance.

You can hear this story on my podcast, American Stories with Rebecca Price Janney at Anchor.fm/rebeccapricejanney

Leave a Reply